How to adjust a key and send good code

Many amateurs miss a lot of fun in ham radio by not knowing the code and how to send it. Sure, they know the code well enough to pass the exam and work a few fellows, but they have never really become operators. Much as we would like to have-some magical short cuts to offer you, we can't; we can only present a few basic principles that have been found to be effective.

How important is it to be able to send good code? For the answer to that, just ask yourself how important it is for you to be understood by the person you are communicating with. If you cannot send good code, then the operator trying to copy you will have just one comment: "Another lid!"

Being able to send readable code is not difficult, but it does take a certain amount of knowhow and practice. This article has two purposes: first, to show the reader how to adjust a key for the best possible code and second, how to send.

Strange as it seems, and contrary to the beliefs of most beginners, the secret of sending good code is learning good code. Most new code men think their primary objective is to increase their speed, when actually it should be to learn the correct code. By correct code we mean the one that's printed in any books on the subject, in contrast to the 5700 varieties one hears on the air. Where does one learn the "correct" code? Easy. By listening to the tape transmissions of W1AW and other stations using tape transmissions, or by listening to the tape transmissions found on the phonograph records offered for learning the code. The correct code, sent by machine or a good operator, has a beautiful basic rhythm that is a far cry from the stumbling, bumbling odd-ball stuff to be found occasionally in the ham bands (and a few other services we can mention). Once you have learned the code from a machine and have acquired a feeling for the basic rhythm, you are on your way toward acquiring a "fist like a tape," because you will be aware of the slightest departures from the correct code. But if you don't know what the code should sound like, you can never hope to pick up your own minor variations and correct them.

The key

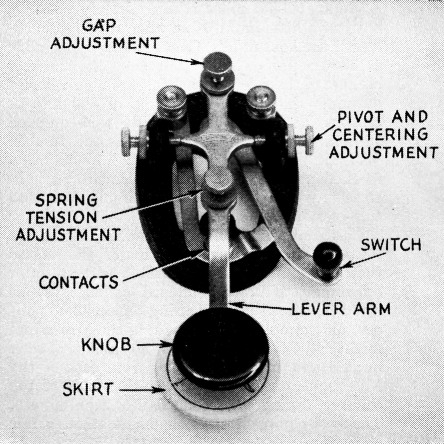

A typical straight key is shown in the accompanying photograph. A telegraph key is simply a lever-type switch that is used to turn the transmitter on and off. When the lever is depressed the contacts close, turning on the transmitter. When the lever is released, the contacts open, turning off the rig.

Most U. S. straight keys are built like this, although some omit the shorting switch. Note the lock nuts at each adjustment. The skirt at the knob is not standard with this key; it was made by drilling a pokerchip.

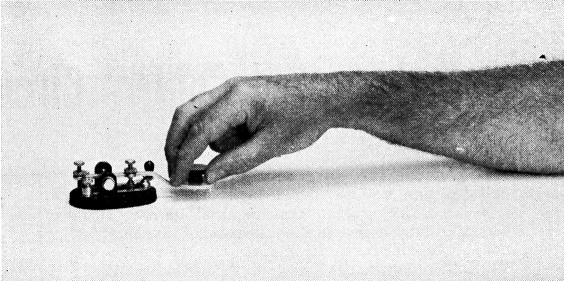

The generally-accepted way to hold a key for minimum fatigue. The wrist is well off the table, and only the forearm near the elbow rests on the table. The finger grip will vary slightly with the length of the fingers and the type of key knob.

The first step in setting up the key is to align the contact points laterally on the lever and base. This is accomplished by setting the pivot adjustment. First, release the lock nuts on the screws and then bring the contact points into alignment. Don't make the screws too tight; allow a slight amount of play to permit the lever arm to work freely. When the screws are properly adjusted, tighten the lock nuts.

The amount of lever travel is a matter of personal preference. However, a good rule of thumb for lever travel is about one-sixteenth inch, measured at the knob of the key. If the travel is less than a sixteenth of an inch it may be hard to control the spacing between and the length of characters. Operators often feel that they can send faster with short lever-travel distances, and in some cases this is true. But it is true only of the operator who sends 25 or 30 words per minute on a straight key, not of the beginner learning the code and not yet able to copy a solid 15 w.p.m. Once you know the code and can handle 15 to 20 w.p.m. easily you can start looking for a magic key adjustment that will catapult you into the 30 w.p.m. bracket, but we'll warn you now that the answer isn't in the key adjustment. The gap adjustment setting determines the lever travel, and the spring tension screw controls the lever tension. If you set the spring tension too heavy your sending is inclined to become "choppy." Similarly, if the tension is too light you are likely to run the characters together, so a little experimenting should be done to find the correct tension. You'll probably find that a lever action on the heavy side will permit you to make more accurate dots. With experience, you'll soon find the correct key adjustments to suit your tastes.

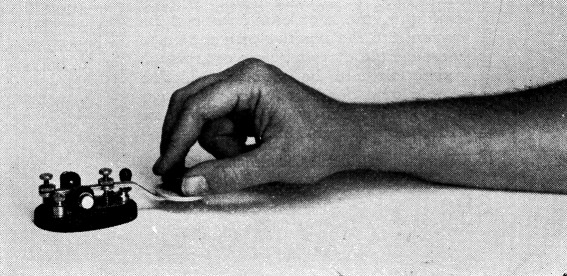

A common error is to rest the entire forearm on the table. This results in rapid fatigue and a glass arm (loss of proper muscle coordination) at an early age.

How to send

Every effort should be made to learn how to send correctly at the very beginning of your amateur career. It is just as easy to acquire good operating techniques as it is to learn bad habits - and habits are very hard to break.

The key knob should be mounted approximately eighteen inches from the edge of the table. By "mounted" we mean screwed down to the table or to a thin board about six inches wide and two feet long. Either system will prevent the key from "traveling." The correct posture for sending is to sit upright in your chair and square with the operating table. Your right arm should be in a line with the key (of course, if you are a southpaw then make it the left arm), and your elbow should rest on the table. The key knob is held on the left side by the thumb, the index finger is on top of the knob and the second finger is on the right side of the key. The two remaining fingers are curled (not clinched!) toward the palm. This method of holding the key is shown in a photograph. Notice that the wrist is not resting on the table, and only the forearm near the elbow rests on the table. The entire attitude should be a relaxed one and the grip should not be tense.

If the table is too high, a sore shoulder may develop in a short time, and a seat cushion would be desirable.

You are now ready to send. First try sending long strings of dits (dots), about ten or more at a time. They should be evenly spaced and should flow smoothly from your key. Once you feel that you've developed a smooth rhythm, try adding dahs (dashes) to your sending. A dah is three times as long as a dit and the time interval between dits and dahs is the same as a dit. Your sending should be almost entirely a wrist action - not fingers or arm, just the wrist. Try to relax and not tense up as you send.

When you find that you can send dits and dahs smoothly you are ready to send characters. One of the easiest and surest methods of sending good code is to say the character as you send it. For example, if you are sending the letter F then say, "di-di-dah-dit" as you send it. You'll be surprised how smoothly you send characters when you do this. The interval between characters is the same as a dah and between words the space is approximately two dahs. A common trouble with newcomers (and many oldtimers are guilty, too) is not leaving enough space between characters and words. Remember that you are attempting to communicate with another party. If you run characters and words together he'll never know what you are trying to say.

The only way to know how correctly formed code sounds is by listening to stations that send good code. There are many stations on the air that use automatic transmitters where the code is run on tapes, meaning of course, perfect code is transmitted. If you are interested in hearing such stations, the Communications Department of ARRL has available a mimeographed list of stations, times, and frequencies. This list includes press, Naval, and amateur stations. The amateur stations listed transmit code practice and while they are usually not taped transmissions, the operators send excellent code. If you want the list, write to the ARRL Communications Department, and ask for form CD-139 and a WIAW operating schedule. Our Headquarters station, W1AW, transmits code practice daily. An excellent method of learning to send good code is to send in unison with WIAW. To do this, you must, of course, know what W1AW is going to send. Every month in QST the material to be sent via W1AW is listed in the Operating News section. This material is taken from previous QST's.

Remember: Don't tense up, develop a smooth rhythm, watch your spacing, and you'll have the satisfaction of hearing hams tell you they like your "fist".

Notes

- The reader who is seriously interested in developing his code ability to the highest proficiency will do well to study Learning the Radiotelegraph Code, a booklet published by the ARRL.

Lewis G. McCoy, W1ICP.